Many in the media seem to have just realized that there is

an armed Shi`i movement in Yemen, and that only after Zaydi Hawthi troops control the capital. And many “analysts”

are seeing the Zaydi return to power in Yemen as an unmitigated disaster, as well as a chance to score political points against

President Obama. The latest historical manifestation of Zaydi resurgence may have positive benefits, however, based

on the following analysis.

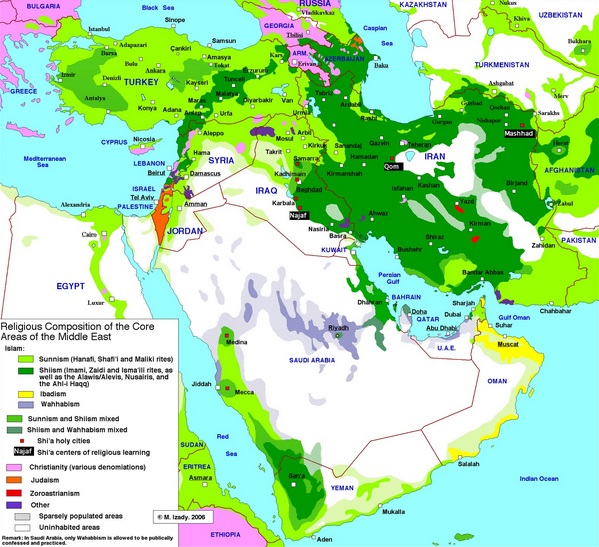

Iran has the world’s largest Shi`i Muslim population;

but Yemen ranks six (and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia tenth). Yemen’s Shi`is, however, are different from those of Iran, Iraq,

Lebanon and Azerbaijan. In sum, for the Twelvers who make up the majorities in those countries, the 12th Imam

disappeared—went into ghaybah, “occultation”—in the ninth century AD and will return before

the end of time (along with the returned Muslim prophet Jesus) to make the entire planet Muslim via both peaceful means and

jihad. For most of the Isma’ilis, who number about 20 million in places like India, East Africa, Yemen

and KSA, there is a living Imam in every age (currently the Karim Aga Khan IV) who traces his descent from the seventh Imam,

Isma’il (thus “Severners”) and who leads the community. The Zaydis of Yemen—who

make up perhaps 40% of the 28 million population there—maintain that the line of Imams should have gone through Zayd,

son of Zayn al-Abidin, rather than through his older half-brother Muhammad al-Baqir. Thus they believe Zayd was the

legitimate Fifth Imam (hence “Fivers”). Zayd, unlike the other early Shi`i leaders—with the notable

exception of Husayn, son of Ali—fomented an ultimately unsuccessful rebellion against the (Sunni) Umayyad rulers of

Damascus which resulted in his death. Zayd’s claims to the Imamate, as well as his fight against what he deemed

unjust Islamic rulers, set a precedent for the Zaydi Shi`a, extant to this day, of a “Hero Imamate” for whom the

Imamate can be achieved or seized, but “neither bestowed nor inherited.” This is in contradistinction to

both the Twelvers, with their “Martyr Imamate,” and to both Twelvers and Seveners for whom each and every Imam possessed, possesses and will possess isma`, or “infallibility.”

(from Fuad Khuri, Imams and Emirs: Stae, Religion and Sects in Islam, pp. 113ff).

The sand is always greener, where the Sunni ranks are leaner.

In some ways the Zaydis, despite being

clearly Shi`i, are the closest to Sunnis theologically—not classifying them as “infidels,” for example—they are if anything farther afield than fellow Shi`is from Sunnis politically, in that they deem “revolt

against the illegitimate Sunni rule as a religious duty” (Encyclopedia of Islam, s.v. “Zaydiyya”).

The first Zaydi concentrations, and indeed polities, were established over a millennium ago in Persia/Iran.

Zaydi da`is, or “missionaries,” were active in Daylam (now Iran’s northwestern Gilan province,

on the southwestern shore of the Caspian Sea) by the 8th c. AD. In 854 a Zaydi state with its capitol in

Amul (modern Mazandaran province, Iran) was established and lasted for some decades, well into the 10th century.

By 900 AD the first Zaydi missionary—al-Hadi ila al-Haqq

Yahya b. Husayn b. al-Qasim (Imam al-Hadi, or sometimes Imam Yahya) had come to Yemen from Iran. He gained converts

among the northern highland tribes, in particular. This Zaydi success in Yemen is all the more surprising considering

that they had, at that point, had little success in state-building even in Daylam. They did, however, have a fairly

developed political soteriology centered around the topic of who was qualified to lead the community. For the Daylami

(Iranian) Shi`a, the characteristics required of the Imam consisted of five core principles: promotion of [Zaydi] Islam, resistance

to tyranny, acting in line with the Qur’an and the Hadith, learnedness in Islamic matters, and some membership in the

ahl al-bayt (“familiy of the prophet”), albeit not rising to the level of strict hereditary descent. In Yemen,

al-Hadi added more prerequisites to the Imamate, such as piety, courage, sword-wielding jihad, asceticism and power to arbitrate.

But there were also posited by him conditions for “limited” imamate, occupied by a “war imam” (imam

fi al-harb) and/or a “knowledge imam” (imam fi al-`-`ilm), because the true Muslim (Zaydi) community

always had to have a living imam extant, however imperfect. In al-Hadi’s time, too, the idea of “emigration,”

or hijra, became even more important in Zaydi Islam than it was in Islam as a whole—both as a religious

duty and the creation of actual fortified mountain villages (or sometimes towns) to which muhajirun could repair.

Such an enclave could serve as a refuge for scholars and adherents of a specific, persectured sect, but was often, also, the

base from which a claimant to the Imamate would launch his mission.

Imam a-Hadi’s Zaydis, thus, waged a double-sided mission of da`wa (proselytization) and jihad (militant

conquest), which was quite successful in the Yemeni mountains vis-à-vis the Sunni tribes and the Isma’ilis

there; but it failed in the important southwestern peninsular city of Najran, despite eight campaigns.

The (ostensible) crest of the Zaydi Mutawakkil

Imamate. Minecraft meets jihad?

A

crucial juncture in the establishment of ideological and practical connections between Yemen and Iran took place in 913 AD

when Imam al-Hadi’s younger son Abu Hasan Ahmad took over the supervision of the Zaydi da`wa and wrote to the Zaydis

in Iran, asking for volunteers to wage jihad. Doing so was presented as a pious and invaluable hijrah, the

idea of which was also disseminated to the pockets of Zaydis inthe Hijaz. The exchange between Yemen and Iran was not all

one way—some Zaydis left Yemen for the Daylam region—but the preponderance of the muhajirun traveled to Yemen,

and continued to do so for several centuries. One major impetus to this transnational Zaydi hijra was when the

Yemen Imam al-Mutawakkil actively encouraged such. By the early 13th century AD (early 7th

century AH), the 11th Zaydi Imam of Yemen, al-Mansur bi-llah Abd Allah b. Hamza, wrangled recognition of the Yemeni Imamate

from the Iranian Zaydis and the two groups then set about cooperating in Arabian pensinsular jihad.

The

rival Isma’ilis were the main targets of the Zaydi jihad, and with the loss of outside support following the collapse

of the Isma’ili Fatimid state in Egypt in the 12th century AD, the Fiver Zaydis gained the upper hand in Yemen—although

pockets of the other branch of Shi`ism survived, most notably in Najran.

The Ottoman

Empire, following its conquest of Mamluk Egypt and the Hijaz in 1517, occupied the mountainous Zaydi areas of “Upper”

Yemen from 1548, but fierce Zaydi resistance drove them out in 1636. The Ottomans came to Yemen the first time, in the

16th century, motivated by an Islamic eschatological fervor championed by the puritanical Sunni movement

in Istanbul known as the Kadizadelis. One salient of this reinvigorated Ottman jihad was aimed at Catholic Christian

Europe, particularly Vienna; the other targetted Yemen, for three reasons: the Zaydis had grown strong enough to pose a legitimate

threat to Mecca and Medina; the Sunni Ottoman Caliph could not brook a powerful Shi`i leader within what was regarded as the

Turkish ambit, nor one whose divine-leadership claims (however outlandish) undercut the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph’s role

as leader of all Muslims; and, finally, because of the importance of Yemen in Sunni eschatological hadith.

Ottoman forces returned in the early 19th century and by 1872 controlled Yemen, remaining

there until the end of World War I. Istanbul had a number of concerns in that region, most notably: British

encroachment on Ottoman domains via east Africa; geopolitical rivalry with the Ottoman’s erstwhile province but increasingly

powerful and independent Egypt; the periodic outbreaks of militant Wahhabism; and control and taxation of both the slave and

coffee trades from east Africa. Several Zaydi Imams led jihads against the Ottoman Turks, and in response by 1911 the Ottoman

expeditionary army numbered 72,000 men and managed to take Sana`a. But shortly thereafter, concerned to stop the Italian

invasion of Ottoman Libya, Istanbul ceded control of northern Yemen to the Zaydis and departed—allowing the Zaydi Imam

Yahya to take the city in 1918.

Yemeni troops and Ottoman officers, c. 1914. Boys 2 Mustachioed Men!?

Yemeni troops and Ottoman officers, c. 1914. Boys 2 Mustachioed Men!?

Ottoman Turkish COIN against the Yemeni Zaydis was quite interesting and could prove instructive to 21st

century conflicts. While the Zaydis led the opposition to the Ottomans, the Isma’ilis vacillated

between supporting the Sunni Turks and their Shi`i cousins. Zaydi intransigence obsessed about the Ottomans’ imposition

of Sunni shari`a over the Zaydi kind, and the installation of Ottoman Hanafi Sunni qadis

(judges)—both grievances which the Hawthi Zaydis have made today vis-à-vis the “Sunni” government

in Sana`a. The “resistance movement among the Zaydi tribes took on some of the strategic

features associated with [later] Maoist guerrilla war… A counter state was established… to mobilize the Zaydi

tribesmen against the Ottoman government, in an ideologically driven guerrilla war designed to expel the Ottomans from Yemen…

This was an Islamic COIN, however, “distinguishing it from the nationalist conflicts of the same period”—one

which “revolved around conflicting views of proper Islamic governance…. The Zaydis (and some of the Isma’ilis)

declared jihad against the Sunni Muslim Ottomans, while the Empire sought to impose traditional, patrimonial rule via army

and bureaucracy…. To that end the Ottoman “information warfare” centered around refuting Zaydi Imamate

claims to legitimacy by, for example, advancing the anti-Shi`i argument that the leadership of the Islamic community had been

taken away from the descendants of Ali and transferred to the Sunni Ottomans, and that the Zaydi Imam should submit to them

because his baghy, or “dissent,” was creating and sustaining fasad,

“immorality” or “corruption” in the ummah. The Ottomans attempted

to use soft as well as hard power, too—building schools that taught obedience to the Caliph and pan-Islamism. Such a

multifarious struggle has parallels in modern Yemen and Arabia, with the the Shi`i actors remaining the same (Zaydis and Isma’ilis)

but the Yemeni government and/or Saudi one standing in for the Ottomans—and the added outside factor of Iran [Vincent

Stephen Wilhite, “Guerrilla War, Counterinsurgency and State Formation in Ottoman

Yemen,” unpublished 2003 doctoral dissertation, Ohio State U.).

Ottoman forces evacuated

Yemen by the end of World War I, and Yemen fell under the British ambit—who acknowledged the Zaydi Imamate’s rule

in North Yemen while retaining Aden as a naval base. Imam Yahya ruled his feudal country as an absolute monarch.

He even was said to have kept the national treasury in a box under his bed. Assassinated in 1948, Yahya was succeeded

by his son Ahmad, who tried to maintain his father’s isolationist and medieval policies. Ahmad died in 1962 and was

replaced by his son al-Badr who was overthrown within a week in a military coup, but the Zaydi Imam fled to London while,

in the northern mountains his lieutenants led a counter-revolutionary movement. For almost a decade the “Republicans”

of Yemen, assisted by 85,000 Egyptian troops sent by Nasser, fought the Zaydis—but the latter were assisted by the Saudis,

who preferred Shi`i “fanatics” to Arab socialists from across the Red Sea.

"No, Private al-Ziskey, aim the bayonet HIGHER--like we do in Egypt."

"No, Private al-Ziskey, aim the bayonet HIGHER--like we do in Egypt."

Egypt withdrew its troops after losing the Six

Days War (1967), and Riyadh brokered the creation of two Yemens which political neutered (or so it was thought) the Zaydi

Imamate. South Yemen, the self-styled “People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen,

which included Aden, was aligned with the Soviet Union during the Cold war; North Yemen, the “Yemen Arab Repubic”

centered on Sana`a, was supported by KSA (and, to some extent, the US) and was largely coterminous with the old Zaydi Imamate.

By the beginning of the 21st (Christian) century, the de facto Zaydi leader in Yemen

was Husayn Badr al-Din al-Hawthi (1956-2004).

Badr al-Din would be killed in battle on September

20, 2004 (along with his wife and son). He was said to have claimed regularly that the

problems not just of Yemenis but of Arabs and Muslims stem from their own sins, most notably the failure to truly implement

Allah’s commands by acceding to secular (Western-derived) systems of government. In this

he agreed with two major 20th century Sunni thinkers, Sayyid Qutb and al-Mawdudi. Also, Badr al-Din shared with many Sunni Islamist ideologues the view that jihad must be utilized and that

branches of Islam that eschew jihadistic efforts to implement the hakimiyah, “rule,” of Allah

are contemptible. Badr al-Din attended the University of Khartoum for several years, where he is

said to have become (more) radicalized, especially toward Israel and Jews, after seeing the media reports of the Israeli “murder”

of the Palestinian youth Muhammad al-Durrah. Afterwards Badr al-Din became in most respects an ardent supporter

of the Islamic Revolution in Iran—although it is unknown whether his tenure in Khartoum exposed him to Iranians, or

the timing is merely coincidental—and seems to have internalized the idea of a Yemeni mass Islamic movement modeled

on Khomeini’s, in which the Zaydi Shi`a would serve as the vanguard. Curiously however,

Badr al-Din was said to have disliked the key component of the IRI’s political ideology—vilayet-i faqih, “rule of the [Islamic] jurisprudent”. His main corpus of writings, the Malazim, utilizes

the Qur’an as a “blueprint” for fighting against those who wish to exploit

the resources of the Islamic world. In this, al-Din greatly resembles the founder of the Islamic

Republic of Iran (as well as any number of Sunni ideologues). Badr al-Din may have been consciously

striving to create an Islamic discourse that was neither strictly Sunni nor Shi`i but contained elements of both.

Upon Badr al-Din’s

death in 2004, his elderly father took ideological control of the movement. Reportedly he had lived for a time in Qom,

so it was no surprise that the elder Badr al-Din opposed democracy and advocated a Zaydi, or at least pious Muslim, ruler.

Badr al-Din Senior died in late 2010, and several Zaydi leaders were killed by a Sunni suicide bomber at his funeral.

The overall Zaydi Hawithi leader since has been Abd al-Malik al-Hawthi (b. 1980 or 1981), another son of the elder Badr

al-Din.

Abd al-Malik al-Hawthi, current Zaydi Leader--and wielder of the kindjal.

Abd al-Malik al-Hawthi, current Zaydi Leader--and wielder of the kindjal.

There are clear splits among the

Zaydis about how closely to emulate Iran and its Shi`I, albeit Twelver, government. `Issam

al-`Imad, a Zaydi cleric who is said to have studied in Qom, now has the zeal of the Shi`i convert and pushes a united Fiver-Twelver

front in Yemen. He claims that the Zaydi libraries in Sa`dah nowadays are stocked with Twelver Shi`i tomes, printed in Qom,

and that the Iranian Twelver influence is great.

He also suggests that Husayn Badr al-Din al-Hawthi

might be occulted, not dead, and that that Badr al-Din was not only close to Hasan Nasrallah, head of Lebanese Hizbullah,

but a virtual disciple of Ayatollah Khomeini (founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran). But not

all Zaydi clerics agree with al-`Imad: one Muhammad Abd al-Azim al-Hawthi says that the Hawthi rebels are “apostates”

and not even Zaydis.

Despite such inter-Zaydi feuding, increasingly the battles in

Yemen are between the Shi`i Zaydis and the Sunni jihadists of AQAP, directly. At the same time, The Zaydi conflict has

increasingly spread across the rather ill-defined border from Yemen into KSA, even as Riyadh has had to deal with demands

from Twelver and Sevener Shi`is in other areas of the Saudi realm. Riyadh has a number of reasons to be concerned about

the Zaydis of Yemen: control over the roads between Sa`ada and Riyadh; growing Shi`a influence, or Shi`is themselves

(refugees), on its territory; Iranian exploitation of any and all Shi`is in the Peninsula; and KSA has been experiencing

its own outbreak of eschatological fervor, with “lone wolf” mahdis cropping up a number of times in recent

years.

Several years ago, the Saudi

paper “al-Watan” was reporting that Iran had been shipping arms to the Zaydi Hawthis, and training Hawthis at

Quds Force camps in Eritrea, just across the Red Sea. Why would Iran be so brazen?

Reasons for Iran to stir the Shi`I pot in Arabia:

1. Leveraging “persecution” of Shi`is into regional geopolitical influence for Tehran-Qom

2. Appealing

to, and exploiting, historical connections with Shi`is of Yemen and greater Arabia

3. Undermining and de-legitimizing the Saudi

government

4. Strengthening

its strategic position on both sides of the Red Sea

5. Strengthening its anti-Israel Islamic front

6. Searching

for allies wherever they can be found.

Current Zaydi calls for the reestablishment of the Imamate, as well as cooperation with

Iran, seem largely to be a result of their disenfranchisement by Sunni authorities in Sana`a, and their perception of being

trapped between the anvil of the Saudi Wahhabis to the north and the ever-encroaching hammer of AQAP from the south.

Conventional

wisdom right now has it that Yemen’s “Hero Imamate” is being used by the Iranian ayatollahs’ “Martyr

Imamate.” But perhaps it is the other way around. The Zaydis have a historical legacy of ruling much of

the country, and they do have legitimate complaints about Sunni repression. Had the US put any pressure on the Sana`a

rulers to acknowledge Hawthi-Zaydi grievances in recent years, they may not have been receptive to Iranian Shi`i blandishments.

But that Imam has left the well. Now the US needs to find a way to prevent Yemen from fracturing while simultaneously

giving the Zaydis their historical and political due. Maybe, in the process, we can take advantage of the Zaydi hatred

of AQAP. And perhaps a bit of pressure on the Wahhabi fundamentalists in Riyadh and their new King, Salman, could

be a good thing, as well.

Let these chaps have a go at AQAP. They have history on their side!

Let these chaps have a go at AQAP. They have history on their side!